Do atheists have a burden of proof?

Being away from the blogosphere for so long (relatively speaking) has put me at some remove from current debates regarding atheism, and I am only just beginning to catch up. I will mention in passing one trend that appears to have developed as The God Delusion, God Is Not Great, The End of Faith, Breaking the Spell and others have gained in popularity and notoriety--and, it seems, atheism with them. It seems that all one needs to do nowadays to refute atheism is to put the modifier "militant" in front of it--and hey presto! the argument is won. Darwin's Beagle has noted this very trend:

As an experiment, I decided to do a search of Google news using a variety of search terms that included "militant" in their name and comparing what "militant" meant when applied as a modifier to other groups. There was no hits for the search terms "militant Christian", "militant Jew", "militant Judaism", or "militant fundamentalism". There was one hit for "militant Christianity", three hits for "militant fundamentlist", 137 hits for "militant Islam", 90 hits for "militant Islamist", and 15 hits for "militant Muslim". There were 6 hits for "militant atheism" and 5 hits for "militant atheist".I myself have been labeled a "Militant Fundamentalist Atheist," even though I am in possession of no bombs or weaponry, have had no military or paramilitary training or experience, and cannot for the life of me see what there is in atheism (particularly the agnostic atheism I espouse) to be "fundamentalist" about. FSM forbid that an actual argument could be allowed to elbow its way past the ad hominems.

So Islam and its derivatives swamp the number of news articles in which the term "militant" is used. Browsing through the articles, I could not find a single one where the adjective "militant" was used to refer to an Islamist that argued passionately for the acceptance of Islam. Every article dealt with factions of Islam that openly advocated killing Americans, infidels, non-believers, or was in some way or another connected with terrorism.

What I'd like to do, however, is direct you to the blog of Matt McCormick, from the Philosophy department of California State University, who is teaching that university's first ever seminar on atheism. What I want to draw your attention to, though, are two posts of his where he suggests that, in a predominantly Christian epistemic context such as that which prevails in the US, "the lion’s share of the burden of proof" will be on atheists. That is, in a culture in which God-belief is the prevailing belief,

You can’t just opt to believe otherwise at will and be epistemically inculpable. Even if everyone around you believes something completely mistaken like “The sun orbits the earth,” their believing it, and so many of them believing it, puts an tremendous burden of proof on you if you are going to break ranks and form a contrary opinion.In case you were thinking otherwise, McCormick is not engaging in Christian apologetics, or at least he is not trying to. (I think.) As a coherentist, his point is that we are justified in believing that which is coherent with prevailing beliefs, and if our beliefs do not cohere with prevailing beliefs, the onus is on us to show how the prevailing beliefs are wrong. To the objection that we should check that our beliefs correspond with objective reality, McCormick replies:

Evidence, for the most part, is what a person takes it to be. Evidence doesn’t just exist out there on its own. Some phenomena only becomes evidence in virtue of being taken to be indicative of some conclusion by some person. And obviously, different people can take the same phenomena as evidence to contradictory conclusions. Or they can appear to be observing the very same phenomena, but they are actually taking note of very different details and drawing the same or different conclusions from it.In other words, McCormick is arguing that it really won't do for the atheist to simply declare that, in the absence of evidence for the existence of a god, there is no reason to believe that god exists. This merely raises two questions: (i) what would the atheist count as evidence of god's existence?, and (ii) since many theists do believe evidence exists for the existence of god, why should the atheist's interpretation of the evidence trump the theists'? Everything turns, then, on the justification and coherence of one's beliefs. It is up to atheists to show how atheism is more coherent than theism as a worldview.

What do you make of McCormick's argument? My own response is mixed. On the one hand, to return to McCormick's geocentrism example--in which one would be justified in believing that the sun orbits the earth if that is the prevailing belief of one's culture--can we really be justified in believing a falsehood? And I don't accept the claim that even in a god-fearing milieu the atheist bears the lion's share of the burden of proof. The lion's share rests with the party advancing a positive knowledge-claim: this certainly applies to the theist, and it also applies to the strong atheist. It doesn't apply to the weak/agnostic atheist, who lacks belief in gods because there is no evidence that gods exist. Sure, he or she would not be able to say definitively what such evidence would look like, but here's the thing: neither could the theist.

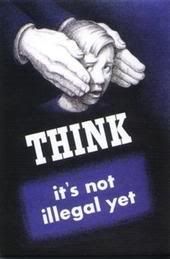

On the other hand, I agree with McCormick that it is not enough for atheists to simply rest on their laurels and expect theists to do all the argumentative leg-work. For one thing, they won't, given that (in societies where theism predominates) they consider theirs to be the default position. Furthermore, to demand reflexiveness on the part of theists whilst neglecting to practice such reflexiveness ourselves is a double-standard. If we have a compelling justification for our position, as McCormick maintains we do, we ought to be out there advancing it.

|