A few remarks on The God Delusion

So much discussion has been provoked by Richard Dawkins' The God Delusion that there seems little more to add--other than to point out that its greatest value may lie ultimately in its ability to stir up debate about the role and place of religious belief--and, let's face it, non-rationalism in all its manifestations--in the secular, liberal and democratic West.

It seems to me that Dawkins has three aims: (i) to provide a defence of atheism (and, by extension, atheists), (ii) to mount an assault upon theism and the undue privileges it is extended in ostensively non-theocratic socities, and (iii) to suggest a Darwinian explanation for belief as sociological phenomenon. I'm not going to provide a more detailed summary here--Wikipedia does a half-decent job of that--but it's probably best to think of The God Delusion as the sum total of all those (doubtless at times caustic and heated) exchanges Dawkins must have had with theists of many stripes over the years, concerning his own strident atheism as well as the viability of their religious beliefs. Indeed, if you cast your eye over to the "Reading Room" section of my sidebar, you'll find a link to an old lecture by Dawkins ("On Debating Religion") which is effectively The God Delusion in a nutshell. (For instance, in the lecture he divides religious people into three categories--"know-nothings," "know-alls" and "no-contests"--the last of which anticipates his critique of the concept of "non-overlapping magisteria" in the book). And if you hang around that very same "Reading Room" long enough, you'll discover that a lot of the ground covered in Dawkins' book had been traversed much earlier by Bertrand Russell--consider, for example, the "Celestial Teapot."

There's nothing wrong with that, of course. As Ninglun suggests, it's a message that needs to be listened to by Americans, as well as--I might add--certain segments of the Australian community also. In an election year in which a PM, whose reign owes some degree of its longevity and success to its ability to woo the religious Right, will square off against an Opposition Leader who has become the de facto leader of the religious Left, it couldn't be more relevant. And the great virtue of Dawkins' book is not just that it makes Russell's arguments (and arguments he has himself advanced on previous occasions) regarding religious belief palatable and accessible, it is that in doing so it remains (for most of the book anyway) downright hilarious and entertaining. His merciless "fisking" of the Bible and of the canonical arguments for God's existence are worth the price of admission alone. (And no, Bill Muehlenberg--simply dismissing Dawkins' deconstruction of these arguments as "sophomoric" and asserting that "his criticisms would not pass a Theology 101 exam" does not a convincing counterargument make. Then again, given Dawkins' opinion of theology as an avenue of human endeavour, would he really care how his treatment of the traditional arguments for God's existence might be regarded by theologians?)

Dawkins' most telling point, I think, is against the advocates of NOMA--the notion that science and religion are "non-overlapping magisteria" and that it is therefore pointless to attempt to account scientifically for God's role in the creation of the universe. For Dawkins, given that science involves by definition the search for natural explanations for natural phenomena, something like the creation of the natural universe is a phenomenon that demands such an explanation. Hence, if it is claimed that the natural universe has a "Creator" ("The God Hypothesis"), such an entity is itself a natural phenomenon and thus fair game for science.

If I have a gripe with The God Delusion, it is with Dawkins' attempt in Chapter 5 to provide a Darwinian/biological explanation for religious belief. It isn't that I don't think such an explanation is credible or interesting--and it is worth noting that Dawkins advances an evolutionary explanation for belief as a hypothesis only. It's just that I'm not sure it really has a place in this book--it's as if Dawkins feels the need to respond to a common ad populum argument against atheism, "How do you explain the fact that the majority of people believe in God?"--and the scientism evinced in this chapter jars with the tone of the rest of the book.

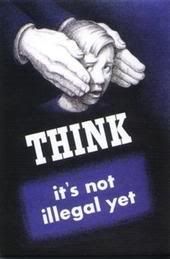

Furthermore, I wonder if Dawkins in his critique of religious belief could have paid more attention to the dangers of other manifestations of faith trumping reason. In Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari wrote: "Hitler got the fascists sexually aroused. Flags, nations, armies, banks get a lot of people aroused." What, after all, is the flag-waving nationalism of Howard's Australia but an instance of religious mania? And can it not--as this post by Bruce suggests--have effects as sinister and deleterious as any religious-inspired conflict?

|