Five Public Opinions?

First, what does the title refer to? It's taken from an aphorism by Nietzsche on the subject of democracy, first published in The Gay Science (aphorism 174), though I'm citing the Nietzsche Reader (Trans. R. J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin, 1977.). Here it is in full:

Parliamentarianism, that is to say public permission to choose between five political opinions, flatters those many who like to appear independent and individual and like to fight for their opinions. In the last resort, however, it is a matter of indifference whether the herd is commanded an opinion or allowed five opinions. -- He who deviates from the five public opinions and steps aside always has the whole herd against him. (267)On that note, I'd like to draw your attention to a recent opinion piece in The Australian by one Ross Terrill, who is a "research associate in East Asian studies at Harvard University." Terrill's article, "Liberty left to the Right"contends that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the "moderate Left was in the vanguard of democracy's surge," while "not a few northern hemisphere conservatives were lukewarm about democracy." Since the 1970s, however, Left and Right have switched roles: the Left, "whose eyes bulge with self-entitlement and whose pale hand is estranged from physical labour," has spurned democratic principles (including "the rights of trade unions in the ALP") in favour of identity politics ("Gays, minorities, women and others"); while "the Right clutches Lady Liberty."

There is plenty of evidence that the Left has forsaken democracy, according to Terrill. The Left spurns "blue collar opinion, which is democracy's soil." The Left opposes "global idealism," which is "liberty's post-communism vocation." Last year, Kerry supporters spoke of moving to Canada if the election went against them. Sydney Morning Herald columnist Alan Ramsey, lamenting Howard's victory, declared that voters had got it wrong. The "liberal" New York Times suggested that the Iraq elections should have been postponed because of threats against it by al'Qaida. The media in Europe and America covered the Davos Forum, "an unelected seminar with not a democratic bone in its body." Ted Kennedy claimed that although the Democrats are the minority party in Congress, "we speak for a majority of the American people." The major Left opposition parties in the US and Australia appear to disagree with President Bush's statement that "The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands."The Left has discovered that "courts help the cause of social engineering more readily than ballots." The Left is attached to the idea of an "international community", and if the "UN chief says US actions in Iraq are illegal, he must be correct, the argument goes, which means the American and Australian majority must be wrong." And "many government leaders sitting at UN sessions have never been elected to their posts." Finally, the Left tells us "how we are going to vote," and then "why we voted."

Don't you just love these cozy false dilemmas? Supposing we were to view the Right as Terrill does as an undifferentiated mass, what kind of democracy does he believe the Right is defending? It can't be liberal democracy: because liberal democracy promotes a balance between the "will" of the majority and the rights of individuals and minorities. Terrill locates the Left's abandonment of democracy in its embrace of minority rights--something the concept of liberal democracy accommodates. It can't be the preferential voting system which operates in Australia, because that is designed to balance the interests of accurate representation with parliamentary and policy stability. Apparently the kind of democracy the Right is defending, if I have understood Terrill correctly, is one in which opposition parties must rubber-stamp every Government bill that is placed before them, and--this is the best part-- must refrain from any criticism of Government policy (the policy of the majority party)--because to do otherwise would be to oppose the will of the majority, and therefore to oppose democracy. Terrill's understanding of democracy, in other words, takes it as given that the electorate supports the party in Government on every issue, simply because that party happened to secure an electoral majority at the most recent election. Music to the Howard government's ears, I'm sure, but I wonder if Terrill would be whistling the same tune if Labor was in power? Or does he expect that a Coalition on the opposition benches would be the forelock-tugging paper-tiger he expects every good democracy-loving opposition party to be?

It's an astoundingly simple-minded vision of what it means to be "democratic," but as smogblot's dissection of Greg Sheridan's reaction to this survey on Australian attitudes to the US reveals, it's a vision that's not likely to be unfamiliar to readers of the national broadsheet.

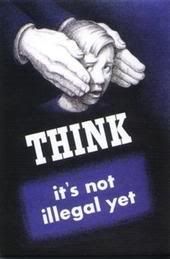

As to what Terrill would think of political engagement outside the parliamentary system (e.g. the anti-war movement, the Baxter protests), I'll leave you to draw your own conclusions. But in any case, even if Alan Ramsey, et al. did lament voters' choices in the recent Federal election, does such a lament really amount to an attack on democracy? If anything, countries such as Australia suffer from a lack of democracy--and that is precisely the state of affairs Terrill and Sheridan wish to preserve. They favour a democracy of disengagement: where "democracy" is something one does once every four years. And then we all go back to our non-democratic workplaces, our non-democratic churches, our non-democratic schools. And politicians return to their non-democratic parties. Is that really sufficient? Here's a thought experiment: if democracy is something we are supposed to value, then what is inappropriate about extending democracy beyond local, state and federal Government to all areas of public life? If, say, the workplace or the chuches are inappropriate arenas for democracy, who's to say that democracy in Parliament isn't equally inappropriate. We can't have it both ways.

|